Review: Daybreak

Daybreak (localised as e-Mission in some languages) is one of my favourite boardgames. It’s a game about climate change made by Matteo Menapace, a brilliant Italian game designer that lives in Britain, and the US game designer Matt Leacock, a veritable boardgame celebrity that authored the bestselling co-op game Pandemic long before the 2020 peak in usage of the word. I had the privilege of getting to know Matteo personally when we worked together on a videogame prototype for Games for the Many, a courageous attempt by the Corbyn-era British Labour Party to leverage videogames for political change. I met him several times at different game fairs, festivals and conferences, and I always found him full of unusual ideas, positive energy, intellectual curiosity. Daybreak is the condensed result of these two minds.

This review is based on the Rules-Play-Culture model.

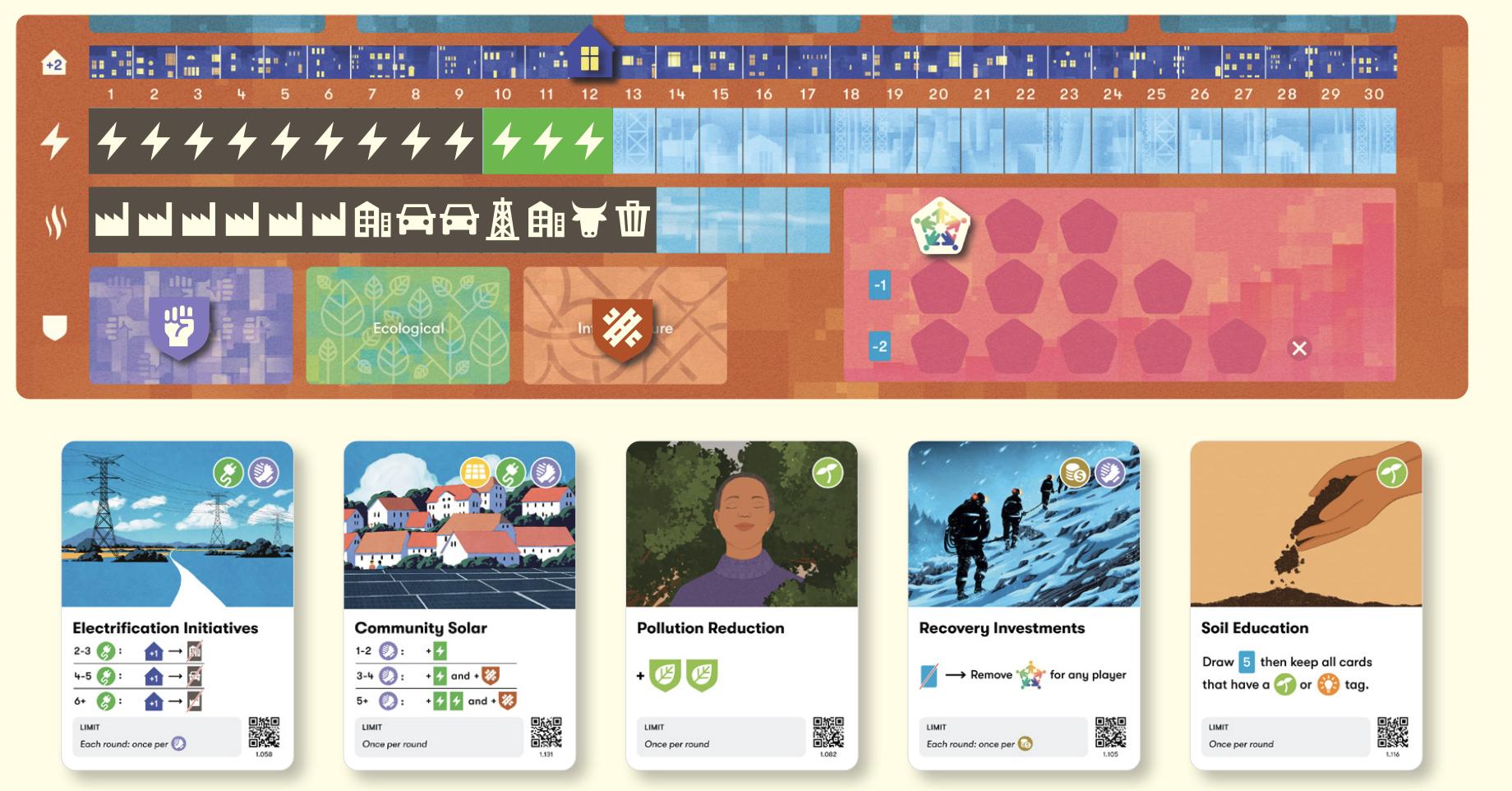

Player mat and Local Projects (from the rulebook, © CMYK)

RULES

Victory condition: Being a cooperative game, the players win together or lose together. They represent “World Powers” (more about this below!) struggling to stop climate change. In order to win, they need to reach Drawdown: a situation in which the amount of Carbon cubes emitted in the last turn is less than the amount of Carbon cubes absorbed. That’s it.

The players lose if they don’t manage to reach Drawdown before one of these catastrophic conditions are triggered:

- any of the World Powers has accumulated too many “Communities in Crisis” tokens.

- the Thermometer has reached a certain threshold;

- it’s taking too long (6 rounds).

The threshold on Communities in Crisis is actually the “true” condition: most matches would get the same outcome with this condition only, because high temperature causes more crises, and cumulative effects cause a defeat if the game drags along for too long. This helps simplifying the rules as a race against the clock to keep in check the accumulation of both Carbon cubes and Communities in Crisis.

Carbon cubes are the main resource, and they are related to Communities in Crisis in many indirect ways. You could quite easily get rid of Carbon cubes if you could freely generate Communities in Crisis, but you cannot unless you want to reach an early defeat. For instance, you could aggressvely cut down “dirty” electricity production that causes the lion’s share of Carbon emissions, but if you produce less electricity than your population’s needs, you get one Community in Crisis token per missing Carbon cube. And the energy needs of your population usually grow at each turn, therefore you need to replace dirty electricity with more green electricity if you want to do it sustainably.

Carbon cubes are generated each turn by a combination of factors, indicated as brown icons on each player’s mat: dirty electricity, polluting industry, farming, extraction, housing, refuse management, transport. The game is very asymmetric, the setup of every player mat is different, according to the real-world geographic and economic differences it models. The brown icons can be removed by player actions, and green-electricity icons can be added with other actions. There is no explicit “green industry” and the like, these emissions are just implicitly replaced by environmentally sound alternatives. Electricity works differently because the authors wanted to model the complex strategic choices regarding green power.

Carbon cubes that are not absorbed at the end of the turn cause several harmful consequences. They directly increase world temperature on the Thermometer, which in turn increases the number of Crisis cards drawn and the number of dice cast to trigger the Planetary Effects. Crisis cards are bad and damage the players in many different ways, but in the end those harms amount to risking to increase your Communities in Crisis. Planetary Effects are very bad and work indirectly as multipliers on the speed of the catastrophe, by changing several parameters when a “tipping point” is reached. This is an avalanche effect similar to those found in the Pandemic series. The distribution curve of the harmful effects is complex and has long tails, like its real-life inspiration.

So, in Daybreak, players have to reduce net Carbon production, aiming for Drawdown, and at the same time prevent an excess of Communities in Crisis. As already explained, Carbon production can be influenced by modifying the energy mix (more green tokens, less dark tokens) and getting rid of the other dark tokens with icons. Communities in Crisis can be prevented by collecting defensive Resilience tokens, and as a last resort by spreading the harm properly among the players – one player with too many Community in Crisis tokens is enough to make everone lose. In order to pursue these goals, the players run Projects, both Global and Local.

Projects are cards. Beautiful cards, with a nice image, some icons on top, and a symbolic description of their effects. The icons on top are “tags”; tags are used as requirements to activate the card, and sometimes the more icons of a certain tag you have, the stronger the card effect becomes. There is also a QR code in the bottom right corner of each card, if you scan it with your phone you can reach a page like this with the full explanation of the real-life equivalent of the Project and its workings in the game. Projects, when activated, influence the other elements of the game, creating or destroying resources, applying transformations, modifying the parameters of a World Power, and so on. Cards can mostly be used on Local Projects in one of three ways:

- Support an existing Local Project, by tucking a card below an existing stack. This gives more stack tags, which can make the effect stronger, or prepare to fulfill the requirements of another alternative Project.

- Spend cards to activate a Local Project that requires it.

- Start a new Local Project, by placing a new card on top of an existing stack. The tags of the cards below are used to fulfill the requirements of the new Project or to make it stronger.

Basically this is how the whole system works. There are other details in the rule that provide means to directly collaborate across players, like cards being used for Global Projects instead of Local Projects, or to weaken or prevent Global Crisis, or donated to other players under certain conditions.

PLAY

The main choices in the central game loop are like:

- Should I use this card to start a new Local Project or keep it to fuel something else?

- Which Local Projects should I activate and in which order?

- How much should I spend in Resilience, in Global Crisis prevention, in Global Project development?

- How am I going to support the increased energy demand next turn?

This kind of choices make it feel a lot like picking a policy mix. Part of it is keeping a balance, mostly between rushing towards the victory condition and putting some resources aside as emergency backup (through Resilience or investment in cutting down the likelihood of destructive crises). Part of it is choosing a road map to pursue, and implement it in the proper order.

Sometimes, short-lived engines are built, when an action enables another action that in turn modifies your status in a more beneficial direction, but usually this cannot be iterated more than two or three times. For instance, you might use Universal Public Transport to get rid of a dirty Transport token by increasing your Energy Demand, and use Thermal Solar to increase your green Energy production to compensate for the increase in demand; the latter would cost you discarding one card, which you can usually afford. If you happen to have managed to start the corresponding Local Projects with the right tags, you have created a combo engine that reduces your Carbon emission by 1 per card discarded. Unfortunately, you cannot overuse this because, even if you are playing the SUV-obsessed United States, you won’t have more than 5 dirty Transport token; once you have removed them all, the combo turns useless and the Project slots, cards and tags have to be recycled into something else. This is one of the many ways used by the game designers to teach you that there is no silver bullet to tackle the climate crisis.

At every turn a new hand of cards is drawn from a very large deck. Most cards are unique. This gives a refreshing feeling of possibilities opening up, but at the same time it can be frustrating for players who are aiming at building a powerful engine that requires a specific tag; cards can be kept in hand from previous turns, which facilitates this kind of long-term attempts. “Useless” cards – useless in the current situation, not useless per se – can always be spent to activate Projects or for their tags. It’s the rare case when a card drawn has no use whatsoever.

The main phase of the game is played simultaneously by all players who examine and play their own cards, and occasionaly give cards to each other (some Projects allow this). No “alpha player”, however tyrannical they may be, can realistically check the hands of everyone else and tell them what to do, which prevents one of the typical issues that plague co-op games.

You don’t really make intercontinental card combos with other players in Daybreak, which is probably a defect theme-wise but a better solution for gameplay. International co-operation is modelled through the Global Projects. Actually, the main areas of collaboration are Global Projects and crisis management, where co-operating takes the form of sacrificing for someone else: either you give up a card to activate a Global Project or prevent a Global Crisis, or you choose to take the hit when there’s a tie with another player in the criterion to pick which World Power is harmed by the effects of a crisis. This gives the collective effort the feeling of a shared burden where everyone has got to do their homeworks to contain the negative consequences of failure or delay.

The ticking bomb of global heating with its looming risk of runaway cascading effects builds up anxiety, and if the party manages to defuse it by a hair’s breadth, the effect is exhilarating. Every now and then, the players are too good and lucky from the onset and the climate never seems to really get out of control; this leads to a smooth win that is not as satisfactory. More often, the situation looks catastrophically doomed from the very first turns; usually, this is not due to bad luck but some significant mistake by at least one player, but because there is no room for alpha players the only way to prevent this is giving general advice to the Powers who are lagging behind; since those are often China or the Majority World, it may end up sounding like richsplaining, which can create… interesting situations if you role-play a bit (Europe: «Tsk, would you please update your power grid, Third World? As much as your kids enjoy digging coal with their bare hands». Majority World: «You’re not growing as fast as I am, snobs. We are BILLIONS, not a bunch of empty villages on the Alps. Also, you may be all wind and solar and compostable bamboo straws for your cocktails, but look at the huge line of brown tokens below that!»).

Card art for Local Project Fossil Fuel Nationalization (from the card reference, © CMYK)

CULTURE

The rules structure and gameplay experience of this game are clearly constructed to be instrumental in delivering a political message. This is a game about what we need to do as a species to fix our political institutions in order to have them fix the climate. I love the idea of games conveying political messages, but I don’t stumble every day into a game that does it so craftfully and with politics that align so well with mine. If for any reason you believe that games should never deal with political issues, first of all you are deeply wrong and shallow and I feel sorry for you, but secondly, you may still appreciate this game and gradually change your mind. Extreme weather events and worldwide catastrophic developments of the climate crisis might help you in realising that you should pay more attention to the politics of climate change.

At the same time, this is also a game committed to be educational about how the science of climate change works. Obviously, making a game that works both as a rough simulation of the climate system and a captivating game experience takes some poetic license, but the main aspects of the problem are represented correctly. The authors made a lot of effort to follow the scientific consensus and this is well documented in their dev logs and in the short essays linked by the QR codes on the card themselves.

I particularly like the explanatory power of the carbon emission-sequestration-accumulation system. Zeroing the carbon emissions looks, and is, a Herculean task that can never be attained by humankind. There is no reasonable way to reduce our carbon emissions to nothing, and this is sometimes used to promote skepticism and inaction. However, no one has ever seriously suggested that we reach Gross Zero; nature absorbs a huge amount of glasshouse gases every day, we just need to emit less than this amount. At the same time, we need to take care of the environment so that this natural absorption power is not crippled. This is clearly represented in the game in the turn phase when several emitted carbon cubes are sequestered by the ocean and tree tokens, and only the outstanding cubes go filling the eerie Thermometer.

The designer Matteo Menapace has explained in detail why they chose Drawdown instead of Net Zero, and I will not repeat his convincing argument. I will add on top of it that explaining that negative net emission is possible as soon as we modify the political landscape of the planet gives a lot of hope and sense of open possibilities. We can literally reverse the damage done, the world is not “ending”, the point is how much avoidable death and suffering we will endure to get our planet back. Aiming at Drawdown helps the delivery of this message that is both mildly optimistic and a call to urgent action. Preaching doom never triggers resistance and fightback.

Part of the care for the educational aspect is the effort put in minimizing the carbon footprint of the game itself. In the game box there are no plastic component and no textiles, and yet the pieces and mats are high quality and lovely to touch. I’m not a big fan of the “carbon footprint” concept, a PR stunt consciously pushed by the fuel multinational BP to shift the blame onto individual consumers, but I appreciate how this product can be used as a practical example of how things can be made differently.

Choosing your avatar, “who you are” in the game world, is a key element of crafting a gaming experience in the digital-game world. This applies to board games too, often in a subtle way, although the players’ avatars are often invisible, or multiple, or very abstract. In Daybreak, every player is a World Power. Four World Powers are defined: USA, Europe, China and the Majority World, the last being an umbrella term to indicate every other country outside those mentioned above, but with an implicit focus on underdeveloped, more agricultural economies (imagine Egypt, Indonesia or Bolivia, not Canada or Japan). It’s a simplification but it’s useful because it represents different real-world scenarios and allows for asymmetric play.

However, what does it mean that you “are” the United States, for example? Actually, the players play as the governments of this country. This game is strictly political also in the sense that it is not about individual action against climate change, it is about collective action, governmental policies. Preaching individual action is a posture that I personally consider in the best case insufficient, in the worst case flatly harmful. We need to show what must be done on a global scale. Still, the game was physically produced using materials and processes that minimise its environmental impact – no plastics etc. Thoughtful and thought-provoking.

So, you play as the government of, say, the United States. Are you Donald Trump or Joe Biden? None of the likes. The premise of the game is that somehow social movements, working-class coalitions, even political revolutions have reshaped world politics and the governments now want to stop climate change. You could make very interesting games about how the powers that be don’t want to do that, or how even a progressive government would need to overcome strong resistance by capitalist monopolists and other vested interests (Molleindustria’s Green New Deal Simulator is a videogame just about that). Daybreak leaves this part – the battle we are currently still fighting in the real world – behind the scenes, its story starts at day one after a global political landslide has triggered real change: the daybreak of a new era in our relationship with nature, and each other.

I cannot help mentioning that the game was at the centre of a significant political controversy after winning the Kennerspiel des Jahres prize (“Connoisseur’s Game of the Year”) in 2024. The fair was during the 2023-2025 Gaza genocide. Matteo Menapace was sporting a Palestine-shaped watermelon pin, to raise awareness for the plight of Palestinian people. Since the fair was in Germany, where every support for Palestinian struggles and liberation is maliciously conflagrated with antisemitism, he was falsely accused of anti-Jewish hate imagery, which is completely ridiculous knowing the guy. He was banned for life, apparently, from taking part in the event, a truly shameful decision by the fair organisers. He explained his position and I believe he deserves a lot of respect for that, this incident is risking to affect his career and he surely knew that there was this possibility but he decided to do it anyway for a cause he believes in.

Many Project cards in the game take a political stance, which is both inevitable and healthy for a game like this. Unsurprisingly, in combination with the Spiel des Jahres controversy, those cards have attracted the attention of critics of both the openly right-wing “Trumpian” and the liberal-capitalist free-market types. This is part of the “cultural” sphere, according to the Rules-Play-Culture scheme, in which the game lives and on which it exerts its influence. Some cards advocate open borders as a way to increase climate resilience, e.g. Climate Immigration and Inclusive Immigration. Some cards favour collective ownership over private property, e.g. Fossil Fuel Nationalization and Community Ownership. Other cards show the link between climate change and social justice, e.g. Universal Basic Services and Universal Healthcare. The importance of active participation in political struggles and civic groups are highlighted by cards such as Social Movements, Youth Climate Movement, Women’s Empowerment, Resilience Volunteers.

The design of the cards also takes a negative stance on a few controversial topics. Geoengineering is represented in the game, artificial sequestration has also got its own wooden tokens, but it is no silver bullet: they are exposed as weak and/or very unpredictable technologies, that cannot solve much and only delay the problems a bit – precisely like in the real world. Carbon Capture and Storage and various forms of nuclear power are useful in the game, but not strictly required to win; the card description on the website is quite sobering about those cards, particularly the Global Project Nuclear Fusion, an amazing technology if it ever works, but not a viable solution for the current climate crisis with its short timespan. And finally, Matteo Menapace explained that the game does not include a card for “carbon offset” or “carbon credits” because they do not fix any problem on a global scale, they just shift it around.

From my point of view, this is all good and part of the appeal of the game. It’s not escapist, and it’s not neutral. Its optimism contrasts sharply with the dire straits in which the planet currently is. Instead of fostering dissociation and separation between the game table and the world, it makes you want to fix the world in the same way. You just need to find the right moves to take.